In my previous post I explained the flowering of Jewish culture on Persian rule that resulted in the Babylonian Talmud. Unfortunately, like all periods of prosperity, it didn't last (how's that for upbeat?). The Persians and the Byzantines (the remainder of the Roman Empire based in Asia Minor) spent most of the 6th century in a series of devastating wars. So by the year 600 they were exhausted in every sense of the word, making it very easy for the world's newest superpower to burst onto the scene, and that's exactly what the Arab Muslims did.

The Arab people first show up in written history around the year 900 BCE (meaning, of course, they certainly existed before that), and up until the time of Muhammad were essentially synonymous with what we today call Bedouins, the nomads and semi-nomads who live in the desert. In the early 600s Muhammad was a poor man living in the city of Mecca, a trade hub which housed a stone considered holy by the pagan Arabs (the Kaaba stone). Like most nomads, in Arab culture there is a strong emphasis on family and tribal loyalty, which often leads to bitter rivalries between different families (something that can still be seen in the modern Arab world). So the world Muhammad lived in was full of various tribes in a constant state of semi-warfare.

According to Muslim tradition (and virtually everything we know about Muhammad is based on tradition, rather than historical fact) Muhammad received the Quran over a period of years from the angel Gabriel (proof of its divine origin is the quality of its writing, impossible for an illiterate like Muhammad). He began to preach the teachings of this Quran around Mecca, which was met with disapproval, and in 622 Muhmmad and his followers fled to Medina, an event known as the Hijra, which represents the beginning of the Muslim calendar. In Medina Mumhammad was more successful, and after a number of years his expanded band of followers were able to conquer Mecca. Shortly thereafter Muhammad successfully united all the tribes of the Arab peninsula (which history has shown to be a very big deal, given how rarely the Arabs have been unified since then).

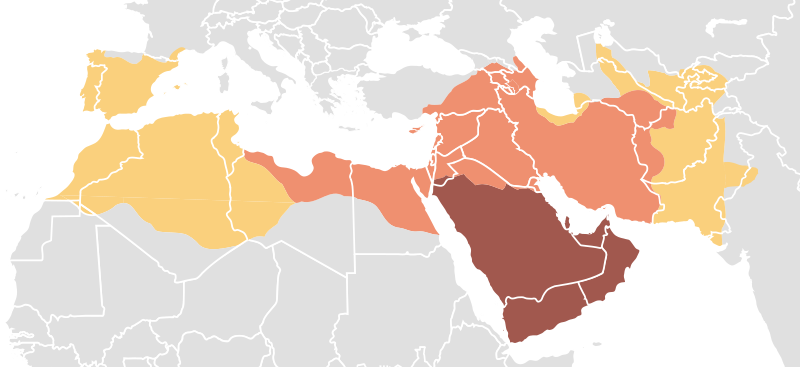

As the Arab-Muslim empire began to expand, Muhammad died, passing on the leadership to a position called the Caliph, which is a combination of spiritual and temporal leader. The first few Caliphs are generally agreed (among Muslims) to have been good leaders, after which accounts start to differ. At any rate the first major dynasty to rule this new (and rapidly expanding empire) was called the Umayyad dynasty. Under the Umayyads the Arab-Muslim Empire reached its greatest extent (in around 750), which is shown below.

Compared to the Roman Empire, which took 1000 years to reach its peak, the Arab-Muslim Empire practically exploded onto the scene, helped along by the constant fighting between the Persians and Byzantines. But the Arabs, who were used to living as nomads/semi-nomads, had no experience governing large territories, so the burden/privilege of governance often fell on the same people who had been governing for years, with the Arab conquerors simply cracking the whip (I mean that figuratively, though I'm sure there were literal instances as well). By the time the Abbassid dynasty, which had replaced the Umayyads everywhere except for Spain (more on that in the next post), there were many non-Arab Muslims holding important posts. The Persians, especially, adopted the Arabic script and Muslim religion and mixed them together with Persian culture and governance. It was this milieu that led the Islamic civilization (which it's no longer really accurate to call Arab-Muslim, in my opinion) to the staggering heights it reached at its zenith in the 9th century. For hundreds of years Islam carried the torch of civilization while Europe recovered from the end of the Roman Empire, exemplified by the House of Wisdom built by the Abbassids in their new capital of Baghdad.

So what exactly did these Muslims believe? First of all, they don't see Muhammad as having received anything new. In their view God had given the same message to Abraham, Moses, Elijah, Jesus, etc., but in each instance it was gradually lost. Therefore, virtually anyone who's considered holy by Jews or early Christians is also holy in Islam. From a Muslim viewpoint Muhammad is simply the last prophet, and this time the message didn't get lost.

The essence of Islam is expressed in five "pillars." The first is a simple declaration of faith; Allah is God and Muhammad is his messenger. The second requires Muslims to pray five times a day. You can actually hear the beautiful call to prayer from our Arab neighbors here at Kibbutz Tzuba (and, truthfully, the call is a lot more beautiful in the middle of the afternoon than it is at 5:30 in the morning). The third requires Muslims to fast during the daylight hours during the entire month of Ramadan (which, compared to the secular calendar, moves each year because the Muslim calendar is lunar, like most non-agricultural peoples). The fourth is the requirement to give charity (2.5% of your savings per year if you have above a certain amount). The final requirement is to complete the Haj, a pilgrimage to Mecca, at least once in your life if you're able.

As you can see, there are quite a few similarities between Muslim and Jewish beliefs. For example, Muslims and Jews both believe in one God, rather than the more complicated trinity worshiped by Christians (I'd like to be clear that Christians still certainly consider themselves monotheists, it's just more theologically complicated). But compared to pagans, all three of the Abrahamic faiths are quite similar, and so when Muslims conquered the world they gave a special status to the "peoples of the book" (Jews and Christians) known as Dhimmi. This status gave people of the book the right to live in Muslim society, though often with additional taxes and restrictions. Speaking very broadly, historically it has been better to be Jewish in a Muslim society than in a Christian one.

The Arab people first show up in written history around the year 900 BCE (meaning, of course, they certainly existed before that), and up until the time of Muhammad were essentially synonymous with what we today call Bedouins, the nomads and semi-nomads who live in the desert. In the early 600s Muhammad was a poor man living in the city of Mecca, a trade hub which housed a stone considered holy by the pagan Arabs (the Kaaba stone). Like most nomads, in Arab culture there is a strong emphasis on family and tribal loyalty, which often leads to bitter rivalries between different families (something that can still be seen in the modern Arab world). So the world Muhammad lived in was full of various tribes in a constant state of semi-warfare.

According to Muslim tradition (and virtually everything we know about Muhammad is based on tradition, rather than historical fact) Muhammad received the Quran over a period of years from the angel Gabriel (proof of its divine origin is the quality of its writing, impossible for an illiterate like Muhammad). He began to preach the teachings of this Quran around Mecca, which was met with disapproval, and in 622 Muhmmad and his followers fled to Medina, an event known as the Hijra, which represents the beginning of the Muslim calendar. In Medina Mumhammad was more successful, and after a number of years his expanded band of followers were able to conquer Mecca. Shortly thereafter Muhammad successfully united all the tribes of the Arab peninsula (which history has shown to be a very big deal, given how rarely the Arabs have been unified since then).

As the Arab-Muslim empire began to expand, Muhammad died, passing on the leadership to a position called the Caliph, which is a combination of spiritual and temporal leader. The first few Caliphs are generally agreed (among Muslims) to have been good leaders, after which accounts start to differ. At any rate the first major dynasty to rule this new (and rapidly expanding empire) was called the Umayyad dynasty. Under the Umayyads the Arab-Muslim Empire reached its greatest extent (in around 750), which is shown below.

|

| stages of Muslim conquest |

So what exactly did these Muslims believe? First of all, they don't see Muhammad as having received anything new. In their view God had given the same message to Abraham, Moses, Elijah, Jesus, etc., but in each instance it was gradually lost. Therefore, virtually anyone who's considered holy by Jews or early Christians is also holy in Islam. From a Muslim viewpoint Muhammad is simply the last prophet, and this time the message didn't get lost.

The essence of Islam is expressed in five "pillars." The first is a simple declaration of faith; Allah is God and Muhammad is his messenger. The second requires Muslims to pray five times a day. You can actually hear the beautiful call to prayer from our Arab neighbors here at Kibbutz Tzuba (and, truthfully, the call is a lot more beautiful in the middle of the afternoon than it is at 5:30 in the morning). The third requires Muslims to fast during the daylight hours during the entire month of Ramadan (which, compared to the secular calendar, moves each year because the Muslim calendar is lunar, like most non-agricultural peoples). The fourth is the requirement to give charity (2.5% of your savings per year if you have above a certain amount). The final requirement is to complete the Haj, a pilgrimage to Mecca, at least once in your life if you're able.

As you can see, there are quite a few similarities between Muslim and Jewish beliefs. For example, Muslims and Jews both believe in one God, rather than the more complicated trinity worshiped by Christians (I'd like to be clear that Christians still certainly consider themselves monotheists, it's just more theologically complicated). But compared to pagans, all three of the Abrahamic faiths are quite similar, and so when Muslims conquered the world they gave a special status to the "peoples of the book" (Jews and Christians) known as Dhimmi. This status gave people of the book the right to live in Muslim society, though often with additional taxes and restrictions. Speaking very broadly, historically it has been better to be Jewish in a Muslim society than in a Christian one.