Today we got back out of the classroom and headed out into Eretz Yisrael (ok, well, the Israel Museum). To start things off I mentioned that Naftali Bennet, leader of The Jewish Home political party, which predominantly represents the Modern Orthodox, suggested that he might consider giving Diaspora Jews some sort of semi-citizenship. All of the students agreed this is a really interesting suggestion (and I certainly agree). The idea could be a great way to make the state of Israel even more relevant for Am Yisrael, though it certainly carries challenges with it (I have a hard time believing I'd want a Jew living abroad to have much say in whether I get sent into a war, for example). According to the article there are currently attempts to hash out this idea. What do you think? Should all of Am Yisrael get some sort of official say in the state of Israel?

We also spoke about this article, which contends that there is a growing trend among the Modern Orthodox to get married outside of the Rabbinate (though still according to halacha). In Israel, there are only religious weddings. There is no such thing as a civil ceremony. Among other things, this means that I, who am not Jewish according to traditional halacha (Jewish law) because my mother is not Jewish (she actually has a Jewish father, was raised Christian and underwent a Reform conversion), cannot get married in Israel unless I undergo an Orthodox conversion (on a side note I do not recommend trying to tell my mother that either she or I am not Jewish; she'll probably punch you). As you would expect secular Jews (like my fiance) and liberal Jews (like me) have long thought this is an unfair system. What's new, at least to my knowledge, is the the Modern Orthodox feeling this way.

While it's new, perhaps it shouldn't necessarily be surprising. In the US, separation of church and state is enshrined in the Constitution. It's well known (and many of the students said it today) that a big part of the reason for this separation is to prevent religion from influencing the government. But if you look back at the discussion surrounding the issue at the time it's clear that many religious leaders felt that mixing government and religion was also bad for religion, often leading to corruption. It seems to me that this new trend among the Modern Orthodox is related to the fact that, as a political institution, the Rabbinate is often seen to be corrupt and/or ineffective (like so many religious institutions that become a part of the government).

Returning to the historical part of our class, today I essentially told the students that Santa Claus isn't real (gasp!). We began by talking about the division within Am Yisrael after the introduction of Hellenism to the region. Much like modern day Jews in America, there were some Jews who quickly acculturated and adopted many aspects of Hellenism, while others rejected it. This, over the next few hundred years, led to the development of different political parties, partially based on how pro-Hellenism they were.

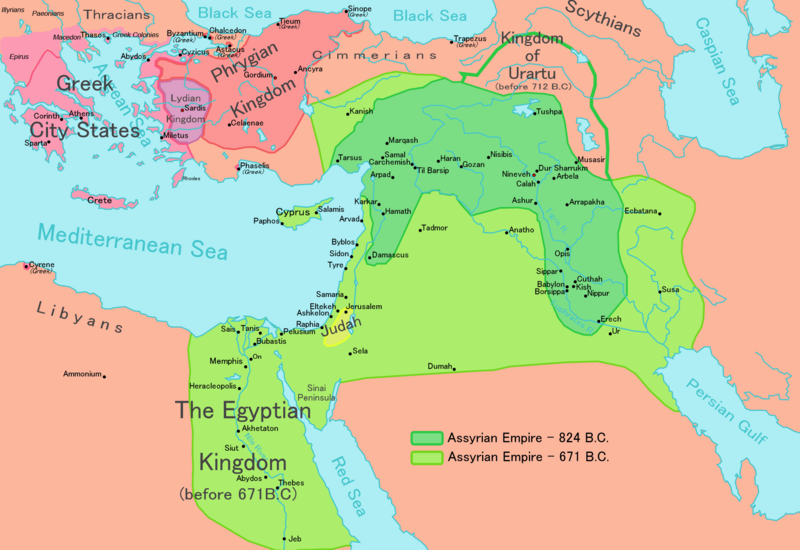

After Alexander the Great died his empire fragmented, and by around 200 BCE Judea was controlled by the Seleucid Empire, which was based in Asia minor. Around this time Menelaus (a Jew, though you can tell from his name how pro-Hellenism he is) offered the ruler of the Seleucids, Antiochus Epiphanes (the bad guy in the Hanukkah story), a hefty sum in return for being named high priest. He also probably appealed to Antiochus's Hellenist tendencies, telling him he would help Hellenize Judea. Shortly afterward Antiochus was involved in a war in Egypt, and rumors started floating around Judea that he had died. This led to a revolt against Menelaus, Antiochus's appointee. Having been rebuffed in Egypt Antiochus returned to the revolting Judea (I imagine in a rather angry mood) and, with Menelaus's help, wreaked havoc. Then, as a punishment, Antiochus imposed of rules forcing Am Yisrael to give up Judaism, such as forbidding circumcision and forcing everyone to sacrifice to the Greek gods (avodah zarah alert!). This was unusual for the Seleucids, who in general adopted a "live and let live" policy, in which they didn't force their beliefs on the peoples over whom they ruled. Aside from simple punishment, it seems clear that Menelaus and the pro-Hellenist faction supported much of this behavior, and the following conflict may well have been as much a civil war as it was oppression from a foreign overlord.

According to the first book of Maccabees (there's more than one) there was a family that lived in Modi'in called the Hasmoneans. The head of the family, Mattathias, was a priest, and when Antiochus's officials told him to worship foreign gods (and offered to make it worth his while to set a good example for the rest of the community) he revolted, killed the official, and he and his sons fled into the countryside. The Hasmoneans, led by one of the sons, Judah Maccabee (Judah the Hammer), led a guerrilla war against the Seleucids for three years, finally recapturing the Temple in 164 BCE. During the fighting we see that, originally the Jews aren't fighting on Shabbat, which turns out not to be a great military strategy. When Mattathias allows fighting we learn the concept of "pikuach nefesh", which tells us that you can violate virtually any commandment for the sake of saving a life (with important exceptions such as murder and defaming HaShem).

During the fighting Am Yisrael hadn't been able to celebrate one of our most important holidays, Sukkot. So after retaking the Temple and re-dedicating it (the Hebrew word for this is Hanukkah) the Hasmoneans celebrated the holiday they had missed (which happens to last 8 days when we include the special holiday at the end of Sukkot). An oppressive Greek overlord (with some Jewish help), a revolt mostly led by Judah Maccabee, a re-dedication of the Temple, sounds a lot like the Hanukkah story to me, but as I'm sure many of you have noticed, we're missing the part about the oil lasting for eight days. With the students I explained the discrepancy shortly afterward, but here I'll leave it for the next blog (I know the suspense must be killing you).

We then went and checked out the model of 2nd Temple Jerusalem. It's pretty awesome.

We also spoke about this article, which contends that there is a growing trend among the Modern Orthodox to get married outside of the Rabbinate (though still according to halacha). In Israel, there are only religious weddings. There is no such thing as a civil ceremony. Among other things, this means that I, who am not Jewish according to traditional halacha (Jewish law) because my mother is not Jewish (she actually has a Jewish father, was raised Christian and underwent a Reform conversion), cannot get married in Israel unless I undergo an Orthodox conversion (on a side note I do not recommend trying to tell my mother that either she or I am not Jewish; she'll probably punch you). As you would expect secular Jews (like my fiance) and liberal Jews (like me) have long thought this is an unfair system. What's new, at least to my knowledge, is the the Modern Orthodox feeling this way.

While it's new, perhaps it shouldn't necessarily be surprising. In the US, separation of church and state is enshrined in the Constitution. It's well known (and many of the students said it today) that a big part of the reason for this separation is to prevent religion from influencing the government. But if you look back at the discussion surrounding the issue at the time it's clear that many religious leaders felt that mixing government and religion was also bad for religion, often leading to corruption. It seems to me that this new trend among the Modern Orthodox is related to the fact that, as a political institution, the Rabbinate is often seen to be corrupt and/or ineffective (like so many religious institutions that become a part of the government).

Returning to the historical part of our class, today I essentially told the students that Santa Claus isn't real (gasp!). We began by talking about the division within Am Yisrael after the introduction of Hellenism to the region. Much like modern day Jews in America, there were some Jews who quickly acculturated and adopted many aspects of Hellenism, while others rejected it. This, over the next few hundred years, led to the development of different political parties, partially based on how pro-Hellenism they were.

After Alexander the Great died his empire fragmented, and by around 200 BCE Judea was controlled by the Seleucid Empire, which was based in Asia minor. Around this time Menelaus (a Jew, though you can tell from his name how pro-Hellenism he is) offered the ruler of the Seleucids, Antiochus Epiphanes (the bad guy in the Hanukkah story), a hefty sum in return for being named high priest. He also probably appealed to Antiochus's Hellenist tendencies, telling him he would help Hellenize Judea. Shortly afterward Antiochus was involved in a war in Egypt, and rumors started floating around Judea that he had died. This led to a revolt against Menelaus, Antiochus's appointee. Having been rebuffed in Egypt Antiochus returned to the revolting Judea (I imagine in a rather angry mood) and, with Menelaus's help, wreaked havoc. Then, as a punishment, Antiochus imposed of rules forcing Am Yisrael to give up Judaism, such as forbidding circumcision and forcing everyone to sacrifice to the Greek gods (avodah zarah alert!). This was unusual for the Seleucids, who in general adopted a "live and let live" policy, in which they didn't force their beliefs on the peoples over whom they ruled. Aside from simple punishment, it seems clear that Menelaus and the pro-Hellenist faction supported much of this behavior, and the following conflict may well have been as much a civil war as it was oppression from a foreign overlord.

According to the first book of Maccabees (there's more than one) there was a family that lived in Modi'in called the Hasmoneans. The head of the family, Mattathias, was a priest, and when Antiochus's officials told him to worship foreign gods (and offered to make it worth his while to set a good example for the rest of the community) he revolted, killed the official, and he and his sons fled into the countryside. The Hasmoneans, led by one of the sons, Judah Maccabee (Judah the Hammer), led a guerrilla war against the Seleucids for three years, finally recapturing the Temple in 164 BCE. During the fighting we see that, originally the Jews aren't fighting on Shabbat, which turns out not to be a great military strategy. When Mattathias allows fighting we learn the concept of "pikuach nefesh", which tells us that you can violate virtually any commandment for the sake of saving a life (with important exceptions such as murder and defaming HaShem).

During the fighting Am Yisrael hadn't been able to celebrate one of our most important holidays, Sukkot. So after retaking the Temple and re-dedicating it (the Hebrew word for this is Hanukkah) the Hasmoneans celebrated the holiday they had missed (which happens to last 8 days when we include the special holiday at the end of Sukkot). An oppressive Greek overlord (with some Jewish help), a revolt mostly led by Judah Maccabee, a re-dedication of the Temple, sounds a lot like the Hanukkah story to me, but as I'm sure many of you have noticed, we're missing the part about the oil lasting for eight days. With the students I explained the discrepancy shortly afterward, but here I'll leave it for the next blog (I know the suspense must be killing you).

We then went and checked out the model of 2nd Temple Jerusalem. It's pretty awesome.

After showing them a few main features of the city I introduced them to the four different sects into which Jews of the time were divided (partially based on how accepting they were of the foreign Hellenistic culture), but I'll save that for tomorrow's blog. I then had to run off to class, but the students went on to take some excellent pictures with the Ahava (love) sign and then visited the Dead Sea Scrolls. These are the oldest extant fragments from the Tanakh, and I think many of the students were amazed to see that we have solid evidence that the text of our holy book seems to be virtually unchanged for at least 2400 years. Despite the fact that I've lived here for five years I'm still American enough that history that old amazes me, and I think the students felt the same way.