Before Shlomo's (Solomon) death an Israelite named Jerobaum was unhappy with Shlomo's rule, attempted some sort of revolt, and then fled to Egypt. When Shlomo died Jerobaum returned and went to speak with Shlomo's heir, Rehobaum. Jerobaum asked him to lighten the tax burden (if you recall Shlomo required a great deal from the Israelites to build the Temple, his palace and various other building projects), promising eternal support if Rehobaum would only make things a little bit easier for the people. Rehobaum seeks the advice of the elders, who encourage him to accede to Jerobaum's request. Rehobaum then consults his young friends (I like to think of them as the rich kids who's parents never told them "no") who disagree with the elders, advising Rehobaum to tell Jerobaum "My little finger is thicker than my father's loins. My father imposed a heavy yoke on you, and I will add to your yoke; my father flogged you with whips, but I will flog you with scorpions." (1 Kings 12:10-11, JPS translation) Ouch. Unfortunately, Rehobaum, the new king, who should be trying to consolidate his rule takes the advice of his young friends. Great politician, huh?

Obviously, Jerobaum can't accept this, and the 10 tribes of the north secede (~930 BCE) to form the Kingdom of Israel, leaving Rehobaum in charge of the Kingdom of Yehuda (Judah). At this point several prophecies have come true. Shmuel, when the Israelites originally asked for a king, warned them how oppressive a king would be. Hashem, in response to Shlomo's avodah zara (worship of foreign gods) tells him that his descendants will rule over only one tribe. We see here that both of those things have now come to pass. From now on there will be two Jewish states: Israel in the north and Yehuda in the south. After the split the two kingdoms spend several decades fighting each other before arriving at some sort of peace agreement.

According to the Tanakh the kingdom of Israel quickly deteriorates into avodah zarah (worship of foreign gods). In class, for example, we spoke about King Ahab and his Phoenician wife Jezebel, who persecute those who worship Hashem (the story begins toward the end of the first book of Kings, 1 Kings 18 will give you the idea). According to more traditional measures (military/economic power, for example), Israel is clearly the more powerful and successful of the two kingdoms, but is villified in the Tanakh.

It is during this period that the later prophets, such as Amos, Isaiah and Jeremiah become active. The early prophets, such as Shmuel (Samuel) and Natan (Nathan), were part of the leadership structure. In modern terms they provided a sort of balance of power to the kings Shaul (Saul) and David respectively. Eliyahu (Elijah), is something of a transitional character. He attempts to advise King Ahab and his Phoenician wife Jezebel, but they refuse to heed his counsel, and continue worshipping other gods. After a dramatic fight between Eliyahu and several hundred false prophets that leads to the false prophets' death, Eliyah is pursued by Ahab and (especially) Jezebel, who want to kill him. One of my favorite episodes in the whole Tanakh is when Eliyahu, watching the other prophets dance and yell and implore their gods basically tells them "you're doing great guys, just yell a little louder and I'm sure your gods are gonna here." Eliyahu, the sarcastic prophet.

We also looked briefly at the episode after Eliyahu flees, in which he is hiding in a cave and Hashem tells him that there will be no more large demonstrations of power (Hashem had just publicly and convincingly helped Eliyahu prove that Hashem is the one and only God), but Hashem will now be a "soft murmuring sound" (also translated as "a still, small voice", if you want to see the Hebrew it's 1 Kings 19:12). This seems to answer the often asked question, "Why are there no more miracles like we see in the Tanakh?" Do you think Hashem decided to influence the world in a different way, stop actively influencing it completely, or was this simply added later to explain away the lack of big, obvious miracles?

The latter prophets, such as Amos, are definitively not a part of the political leadership. In most cases they're a lot closer to outlaws, railing against the corrupt behavior of Israelite/Judean leaders and citizens. And, whereas the early books of Neviim (the middle part of the Tanakh) such as Joshua and Judges, are written in the narrative style with a clear plotline, the latter prophets use a poetic style and almost never try to recount historical events. They also differ from everything we've read so far in the Tanakh in that they care about how everyone behaves, not just the Jewish people. The first chapters of Amos, for example, make a long list of the iniquities of several of our neighbors. But they don't stop with other nations! They save their harshest criticism for the Israelites. In other areas of the Tanakh the Jewish people are frequently criticized for avodah zarah, worshipping foreign gods (like King Solomon, which we saw in the last blog entry), but in the books of the latter prophets they reserve their harshest criticisms for our failures to treat each other properly. In particular, these prophets are incensed at our false piety and our mistreatment of the weakest members of society. The ideas espoused by the latter prophets form the basis for what is known as ethical monotheism, the idea that the most important aspects of our religion are believing in one god and treating each other properly. This concept will be the basis for much of Reform Jewish thought.

Obviously, Jerobaum can't accept this, and the 10 tribes of the north secede (~930 BCE) to form the Kingdom of Israel, leaving Rehobaum in charge of the Kingdom of Yehuda (Judah). At this point several prophecies have come true. Shmuel, when the Israelites originally asked for a king, warned them how oppressive a king would be. Hashem, in response to Shlomo's avodah zara (worship of foreign gods) tells him that his descendants will rule over only one tribe. We see here that both of those things have now come to pass. From now on there will be two Jewish states: Israel in the north and Yehuda in the south. After the split the two kingdoms spend several decades fighting each other before arriving at some sort of peace agreement.

|

| After Shlomo there are two Jewish states: Israel in the north and Yehuda in the south |

It is during this period that the later prophets, such as Amos, Isaiah and Jeremiah become active. The early prophets, such as Shmuel (Samuel) and Natan (Nathan), were part of the leadership structure. In modern terms they provided a sort of balance of power to the kings Shaul (Saul) and David respectively. Eliyahu (Elijah), is something of a transitional character. He attempts to advise King Ahab and his Phoenician wife Jezebel, but they refuse to heed his counsel, and continue worshipping other gods. After a dramatic fight between Eliyahu and several hundred false prophets that leads to the false prophets' death, Eliyah is pursued by Ahab and (especially) Jezebel, who want to kill him. One of my favorite episodes in the whole Tanakh is when Eliyahu, watching the other prophets dance and yell and implore their gods basically tells them "you're doing great guys, just yell a little louder and I'm sure your gods are gonna here." Eliyahu, the sarcastic prophet.

We also looked briefly at the episode after Eliyahu flees, in which he is hiding in a cave and Hashem tells him that there will be no more large demonstrations of power (Hashem had just publicly and convincingly helped Eliyahu prove that Hashem is the one and only God), but Hashem will now be a "soft murmuring sound" (also translated as "a still, small voice", if you want to see the Hebrew it's 1 Kings 19:12). This seems to answer the often asked question, "Why are there no more miracles like we see in the Tanakh?" Do you think Hashem decided to influence the world in a different way, stop actively influencing it completely, or was this simply added later to explain away the lack of big, obvious miracles?

The latter prophets, such as Amos, are definitively not a part of the political leadership. In most cases they're a lot closer to outlaws, railing against the corrupt behavior of Israelite/Judean leaders and citizens. And, whereas the early books of Neviim (the middle part of the Tanakh) such as Joshua and Judges, are written in the narrative style with a clear plotline, the latter prophets use a poetic style and almost never try to recount historical events. They also differ from everything we've read so far in the Tanakh in that they care about how everyone behaves, not just the Jewish people. The first chapters of Amos, for example, make a long list of the iniquities of several of our neighbors. But they don't stop with other nations! They save their harshest criticism for the Israelites. In other areas of the Tanakh the Jewish people are frequently criticized for avodah zarah, worshipping foreign gods (like King Solomon, which we saw in the last blog entry), but in the books of the latter prophets they reserve their harshest criticisms for our failures to treat each other properly. In particular, these prophets are incensed at our false piety and our mistreatment of the weakest members of society. The ideas espoused by the latter prophets form the basis for what is known as ethical monotheism, the idea that the most important aspects of our religion are believing in one god and treating each other properly. This concept will be the basis for much of Reform Jewish thought.

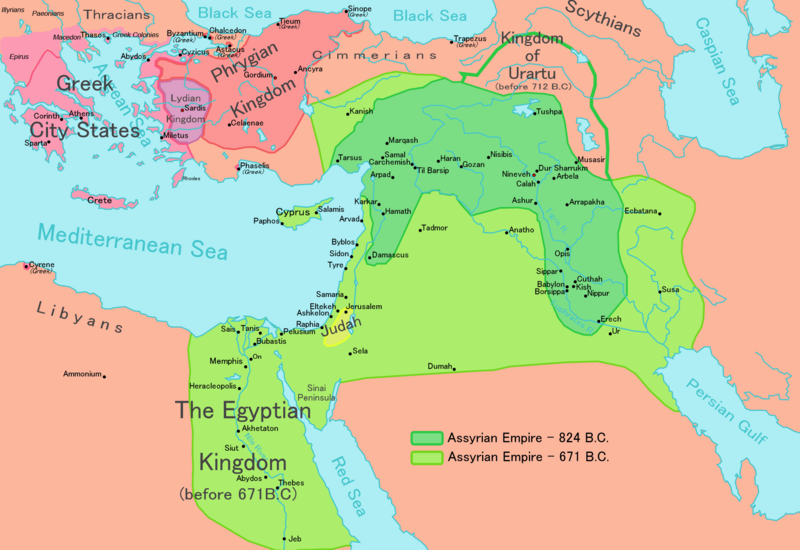

As we would expect the Kingdom of Israel, who is doing avodah zarah and not establishing a just society, is eventually punished. The mechanism for their punishment in this case is the Assyrians, a Mesopotamia-based empire who have a resurgence around 800 BCE.

In 722 BCE the Assyrians conquer Israel. Many of the citizens of Israel were deported, in line with Assyrian imperial policy. This destruction and subsequent deportation led to what is known as the ten lost tribes. As with any area in which there's a war there would certainly have been many people who chose to flee, some of them (if not most) to their southern neighbor, the Kingdom of Judah. As further proof for this phenomenon there is archaeological and historical evidence that the King of Judah at the time, Hezekiah, enlarged the walls of Yerushalayim considerably (the large square-ish part in the picture below), likely in part to accommodate the refugees.

20 years later Hezekiah decided to take advantage of unrest in Mesopotamia (the Assyrian homeland) to throw off the Assyrian yoke and declare independence. Among his preparations he improved the water tunnel to the Gihon spring, which you can see in the picture above. The Assyrians, after dealing with the unrest, arrived to Yehuda and devastated the entire country (such as we see in Lachish, for example). Having destroyed the rest of the country they arrive in 701 BCE to Yerushalayim, which they put to siege (I recommend reading about what it's like to be under siege, for example the relatively recent Siege of Leningrad or even the fictional siege of King's Landing in Game of Thrones, to get a sense of how scary and terrible it is). According to the Tanakh Hashem killed thousands of Assyrian soldiers, causing them to lift the siege and flee back to Mesopotamia. Other sources claim a plague ravaged the Assyrian ranks. Yet others say they left to, once again, deal with unrest in the homeland. All the sources agree Yerushalayim was saved. You can imagine the euphoria in the city as the Assyrians left.

|

| The original city of David (right) and Hezekiah's Wall (left) |

One consequence of the "miraculous" departure of the Assyrian army is that the Yehudans came to believe that Hashem would never allow Yerushalayim, the holy city, to be conquered. Just over a hundred years later the Babylonians (also based in Mesopotamia) were the major power in the region. The King of Yehuda at this time decided to ally with the Egyptians against the Babylonians. Turns out he bet wrong. The ascendant Babylonians arrived to Yehuda and began a siege of Yerushalayim. Despite the prophet Jeremiah's cries to repent and warnings that Yerushalayim would be handed over to the Babylonian army, the King of Yehuda held firm, buoyed by the promises of false prophets (according to the Tanakh, I don't expect I could tell whether a prophet is true or false) and no doubt the memory of the miracle that saved Yerushalayim from the Assyrians. On the ninth of Av (a Hebrew month) the Babylonians destroyed Beit HaMikdash (the Temple); since then this has been a day of mourning for Am Yisrael (Tisha b'Av, the ninth of Av). The elites of Yehuda are sent in exile to Babylon, and after ~600 years living in our homeland in Eretz Yisrael we are sent into Galut Bavel (the Babylonian Exile).

Do you think Am Yisrael deserved this punishment? Is it divine? Is it simply the whim of history? If you heard this about another people, would you expect them to still be around thousands of years later?

It seems miraculous that a people could remain alive thousands of years after being exiled. It may not be a divine force that allowed this to happen, but it definitely is a special force. Perhaps it is the laws given to us that allowed the Jewish people to stay alive, the laws that say that maintaining our religion is more important than our lives themselves. Or perhaps it is the tradition of Judaism that has allowed us to stay alive, traditions that foster a strong community such as celebrating Shabbat every week with family.

ReplyDelete