In order to learn more about the Oral Torah we went on an amazing tiyul (field trip) in the north of the country. We began at Beit Shearim, which is just southeast of Haifa, then cut across the country to Beit Alfa, which is near Beit She'an on Israel's Eastern border, and finished up with a dip in the beautiful Sachne Pools nearby. So why were we up north? After the destruction of Beit HaMikdash in 70 and the Bar Kochba revolt from 132 to 135 Jerusalem and the center of the country were completely destroyed and the center of Jewish life moved to the north. The Sanhedrin, for example, moved among places such as Tzippori, Beit Shearim and Tiberias (and is therefore known as the "Wandering Sanhedrin" during this time). During this time the most important development for Am Yisrael was the continued progression of the Torah she'be'al peh (Oral Torah or Oral law). I explained the principles behind the development of the Oral Torah in a previous post, but it's basically the tradition that was passed down to explain difficulties/incongruities in the written text and to adapt the written Torah to changing circumstances. And by the arrival of the Romans (63 BCE) it was already a prominent part of Jewish thought. The destruction of Beit HaMikdash by Titus basically ended the Sadduccee sect, whose Judaism was based on Beit HaMikdash and who didn't accept the legitimacy of the Oral Torah, leaving only the Pharisees, now the leaders of Am Yisrael, and their academies, the centers where the Oral Law developed.

I've already mentioned a few of the most important Rabbis in this process: Hillel, who applied Hellenistic logic to Jewish law and developed hermeneutical principles (some of which will be familiar to modern lawyers, such as an "a fortiori" argument), and Yochanan ben Zakai, who fled the besieged Jerusalem, established an academy in Yavneh, and began to build a Judaism not based around Jerusalem and Beit HaMikdash. In my previous post I mentioned Rabbi Akiva, spiritual leader of the Bar Kochva revolt, who died gruesomely in an amphitheater while saying the Shema (the central statement of faith in Judaism). Rabbi Akiva is generally credited with beginning to organize the Oral Torah. As you can imagine the main way people studied the Tanakh was in order, beginning with Breisheet (Genesis) and proceeding through Shemot (Exodus), Vaykira (Leviticus), etc. But as we more explicitly defined the goal of study to be understanding which laws can be derived from the Tanakh this wasn't an effective method, so Rabbi Akiva organized the Oral Torah into six books, arranged by subject. Now, to learn about the laws regarding Shabbat, for example, you didn't have to search through several different books of the Tanakh and find the appropriate interpretation; you could simply look at the section dealing with laws about Shabbat.

One of the next major contributors to the Oral Torah (and obviously I'm leaving out many important people) was Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who is the reason we began our tiyul in Beit Shearim, where, according to tradition, he is buried. During the time when Yehuda HaNasi was active (around 200 CE) he noticed at least two main problems with the Oral Torah. First, given the number of Jews who had been killed during the two revolts and the ongoing persecution against Am Yisrael, he recognized the difficulty of depending on the tannaim (who memorized and passed on the Oral Torah), who might be killed at any moment. Second, he saw that as the process of Oral Law drew wider acceptance there were more and more interpretations to the various stories and laws. While this flourishing of Jewish thought certainly had many positive aspects, it also made it more likely for there to be a sect (or sects), such as the Christian Jews, who would eventually break away from Am Yisrael (the Jewish People). Given these realities he made the controversial decision to write down the Oral Torah, which he organized in the six categories developed by Rabbi Akiva and is today known as the Mishna.

Today, it seems quite obvious that writing down the Mishna (or anything else you want to preserve) is a good idea, but there are several problems. The first is that writing down the Oral Torah destroys one of its main advantages: its ability to adapt to new circumstances. Once its written down it loses its flexibility (and we'll see how Am Yisrael deals with this problem in a later blog). Another main concern is that in writing down the Oral Torah Yehuda HaNasi had to decide which traditions/interpretations to include and which to leave out. In explaining this to the students I asked them to consider what they would write today if they had to make an official determination about what is Jewish. Most Jews would clearly describe someone who wears a kippah, prays three times a day, studies Torah and behaves in a morally just way as Jewish, and most Jews would clearly describe someone who goes to church every week and accepts Jesus as his personal savior as non-Jewish. The question is where do we draw the line? Does being Jewish only mean behaving ethically? Does it mean a minimum number of visits to Beit Knesset every week/month/year? Does it mean celebrating Jewish holidays, or speaking Hebrew? If I "feel Jewish" does that make me Jewish? And what conseuqence will our definition of Jewish have for the future of Am Yisrael? It's obviously a very difficult question to answer, and I hope you'll share your own view in the comments.

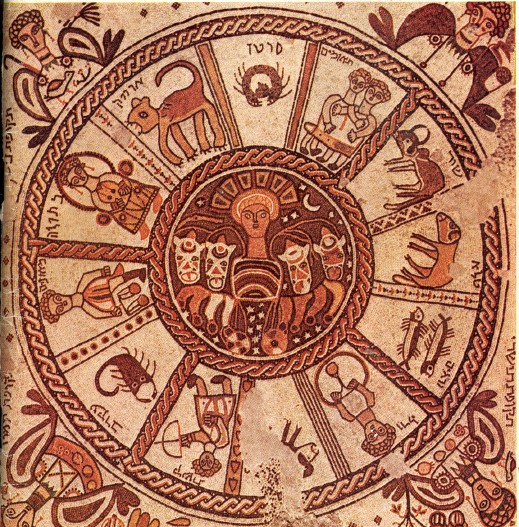

Also on this tiyul we saw what it was like for Am Yisrael to live as a minority among a strong majority culture (sound familiar?) and the influences the majority culture can have. At Beit Shearim we saw rabbis' graves with pictures of eagles, the symbol of Rome, and even Nike, the goddess of victory. At Beit Alpha we saw the beautiful mosaic floor of a Beit Knesset, which had a picture of the Roman sun god Helios in the middle.

After seeing these somewhat surprising images in slightly uncomfortable places I asked the students what they made of it, and how they thought it compared to their modern day lives. Many of them accepted the ubiquity of modern American Christian culture (some of them had sung Christmas songs as part of being in Chorus class; everyone had celebrated Valentine's Day), but still felt like these particular instances were going too far (a foreign god in a beit knesset!). Both of these discussions were incredibly interesting, and I hope the students (and anyone else who's interested!) will share their thoughts in the comments. A few of them also wrote about which cultural practices and symbols we can adapt and use as Jews in their own blogs, so check them out!

I've already mentioned a few of the most important Rabbis in this process: Hillel, who applied Hellenistic logic to Jewish law and developed hermeneutical principles (some of which will be familiar to modern lawyers, such as an "a fortiori" argument), and Yochanan ben Zakai, who fled the besieged Jerusalem, established an academy in Yavneh, and began to build a Judaism not based around Jerusalem and Beit HaMikdash. In my previous post I mentioned Rabbi Akiva, spiritual leader of the Bar Kochva revolt, who died gruesomely in an amphitheater while saying the Shema (the central statement of faith in Judaism). Rabbi Akiva is generally credited with beginning to organize the Oral Torah. As you can imagine the main way people studied the Tanakh was in order, beginning with Breisheet (Genesis) and proceeding through Shemot (Exodus), Vaykira (Leviticus), etc. But as we more explicitly defined the goal of study to be understanding which laws can be derived from the Tanakh this wasn't an effective method, so Rabbi Akiva organized the Oral Torah into six books, arranged by subject. Now, to learn about the laws regarding Shabbat, for example, you didn't have to search through several different books of the Tanakh and find the appropriate interpretation; you could simply look at the section dealing with laws about Shabbat.

One of the next major contributors to the Oral Torah (and obviously I'm leaving out many important people) was Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who is the reason we began our tiyul in Beit Shearim, where, according to tradition, he is buried. During the time when Yehuda HaNasi was active (around 200 CE) he noticed at least two main problems with the Oral Torah. First, given the number of Jews who had been killed during the two revolts and the ongoing persecution against Am Yisrael, he recognized the difficulty of depending on the tannaim (who memorized and passed on the Oral Torah), who might be killed at any moment. Second, he saw that as the process of Oral Law drew wider acceptance there were more and more interpretations to the various stories and laws. While this flourishing of Jewish thought certainly had many positive aspects, it also made it more likely for there to be a sect (or sects), such as the Christian Jews, who would eventually break away from Am Yisrael (the Jewish People). Given these realities he made the controversial decision to write down the Oral Torah, which he organized in the six categories developed by Rabbi Akiva and is today known as the Mishna.

Today, it seems quite obvious that writing down the Mishna (or anything else you want to preserve) is a good idea, but there are several problems. The first is that writing down the Oral Torah destroys one of its main advantages: its ability to adapt to new circumstances. Once its written down it loses its flexibility (and we'll see how Am Yisrael deals with this problem in a later blog). Another main concern is that in writing down the Oral Torah Yehuda HaNasi had to decide which traditions/interpretations to include and which to leave out. In explaining this to the students I asked them to consider what they would write today if they had to make an official determination about what is Jewish. Most Jews would clearly describe someone who wears a kippah, prays three times a day, studies Torah and behaves in a morally just way as Jewish, and most Jews would clearly describe someone who goes to church every week and accepts Jesus as his personal savior as non-Jewish. The question is where do we draw the line? Does being Jewish only mean behaving ethically? Does it mean a minimum number of visits to Beit Knesset every week/month/year? Does it mean celebrating Jewish holidays, or speaking Hebrew? If I "feel Jewish" does that make me Jewish? And what conseuqence will our definition of Jewish have for the future of Am Yisrael? It's obviously a very difficult question to answer, and I hope you'll share your own view in the comments.

Also on this tiyul we saw what it was like for Am Yisrael to live as a minority among a strong majority culture (sound familiar?) and the influences the majority culture can have. At Beit Shearim we saw rabbis' graves with pictures of eagles, the symbol of Rome, and even Nike, the goddess of victory. At Beit Alpha we saw the beautiful mosaic floor of a Beit Knesset, which had a picture of the Roman sun god Helios in the middle.

|

| Part of the mosaic floor in the beit knesset at Beit Alpha showing the god Helios |

The ancient congregation at Beit Alfa carried on traditions when surrounded by other leading cultures. Linking their traditions with the wider cultures of that day is something that I think is very admirable and something we make an effort to do today. The mosaics serve as an example of our assimilated culture back then, for the present, and future.

ReplyDeleteI agree with your view points. The traditions should be carried out today because without doing them, they will be lost.

DeleteOne of the essential questions that is repeatedly asked every history class is—what constitutes religion and what constitutes culture? In this scenario, it is critical to differentiate the two. For example, Roman gods and goddesses, zodiac signs, or Romanesque symbols/designs/architecture inside a Jewish synagogue could be interpreted in contemporary times as a form of disrespect or foreign worship; however, to its inhabitants, perhaps it was just as trivial and quotidian as a modern Orthodox Jew swearing "Jesus Christ" as he stubs his toe on the mikvah. We are constantly being acculturated into other more dominant societies, and the assimilated results always blend religion and culture, the fine line between the two becoming even less distinguishable.

ReplyDeleteWhile I think that it is okay to assimilate in our everyday lives, I think that we need to keep the gods of other religions out of our temple, our place of worship. How can we pray to one god and decorate our temple with another? To put greek gods in our temple seems like a gateway to worshipping other gods, and it could be taken as endorsing the worship of those gods by members of that temple. In my opinion, we can be as assimilated as we want in our daily life, but keep the other religions out of our temple. It's our temple. Let's keep it that way.

ReplyDeleteI think that it is okay that they had different gods in the mosaic. The fact that they were connecting the culture around them to their tradition is very important. It shows that they could adapt while still sticking to their religion. In the present day we have done this as well.

ReplyDeleteFirst of all, relating to the part about some students singing Christian songs in a chorus class or celebrating Valentine's Day, I believe that those two things are fairly different. Singing the songs in chorus, while they may be required, seem to lean more towards Christian religion than American culture compared to something such as celebrating Valentine's Day. Although Valentine's Day was originally derived from Christian ideology, it has adapted to American society and has become more of an American holiday rather than a Christian one. For me, it's interesting to think about how large of an impact American society has on Jews. It can be said with 100% certainty that Israelis don't celebrate Valentine's Day or Halloween or any of those originally-Christian holidays. But some, if not most, Jews in America do, and I don't believe that it makes them/us any less Jewish than the ones that don't.

ReplyDeleteI think being Jewish means something different to everyone, which I know makes defining it extremely difficult, but religion is not one sided, it is complex. I think for Israelis in Israel, all they have to do is live to be Jewish. But, american Jews have to actively practice Judaism to be Jewish without fear of assimilation. I also think Hebrew is a unifier of Judaism and something no other religion has, because no matter where you go, the Torah will always be in Hebrew and even if you don't speak the same language of another Jew you will still be able to recite the Shema with them which is super cool!

ReplyDelete